Why we need global data to solve global problems

COVID-19 didn’t discriminate when it came to race or ethnicity, but health equity did.

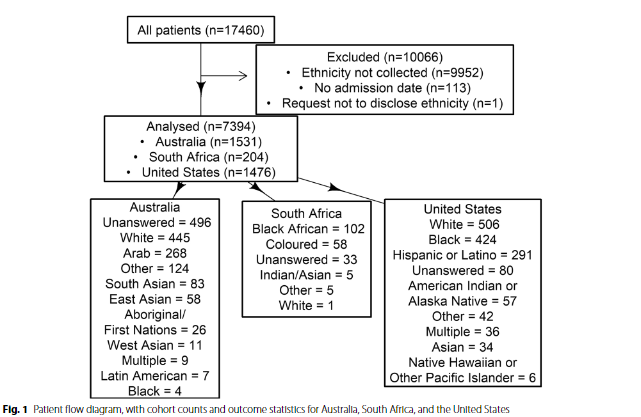

The latest paper by the COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium has been published calling for mandatory ethnicity and social determinants for international research projects. The pioneering manuscript, thought to be one of the first of its kind, required researchers to create a complex methodology to interpret ICU data from patients, providing a lens to analyse COVID-19 treatment outcomes from the perspective of race and related social determinants for the first time.

While improving access to healthcare for ethnic minorities is a public health priority in many countries, little is known about how to incorporate information on race, ethnicity, and related social determinants of health into large international studies.

“If we have learnt anything from the pandemic, it is the importance of multinational studies and research that transcends international borders,” said Associate Professor Matthew Griffee, University of Utah School of Medicine.

“While we may be able to collect data and attempt comparisons across different countries, the impact of this research is severely limited when conversations around race and ethnicity are only from single cities or countries.”

Associate Professor Sung-Min Cho, Johns Hopkins Hospital said the new paper was an important contribution to the field because it is one of the first papers to investigate healthcare disparities across race and ethnicity on a global scale.

“It became evident that racial and ethnic minority cohorts have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 in the United States, especially those with critically ill patients. However, the data only focused on specific country or geography, rather than investigating this important topic on a global scale across different countries.”

Patients from the United States, Australia and South Africa were the focus of analysis of treatments and in-hospital mortality, stratified by race and ethnicity. Even across these three countries, there was a wide variety of race and ethnicity designations, with the paper concluding that disease severity was higher for Indigenous ethnicity groups in the US and Australia than for other ethnicities.

“Not all research is about finding cures and breakthroughs, and it was great to be involved in a study that took the time to consider how we collected data during a pandemic and how we might do it better next time,” said Professor Adrian Barnett, founding member of the Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation.

Professor John Fraser, Director, Critical Care Research Group and Co-Founder, COVID Critical said, “the virus doesn’t care about race, colour nor creed, yet we saw during the pandemic that your access to care varied greatly depending on where you lived. This may not come as a surprise to everyone, but if we don’t have the right data, we can’t answer the big, global questions.”

“Because there is no global system of race and ethnicity classification, researchers designing case report forms for international studies should consider including related information, such as socioeconomic status or migration background,” said Dr. Griffee.

“If nothing else, I hope this paper sparks dialogue around the need for major international research collaborations, and the role they play in preparing us for future pandemics.”

About COVID Critical

Established in early 2020, the COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium (COVID Critical) is a global alliance of healthcare professionals and researchers committed to identifying the most effective treatments for critically ill COVID-19 patients. During the pandemic, the Consortium assembled a database of de-identified data from more than 27,000 patients in 64 countries, creating the largest COVID-19 ICU database in the world. Analysis of the millions of data points continues.

To learn more about COVID Critical click here.